Well, Happy Birthday to James Paul McCartney, who was born this day in 1942 and grew up to be one half of what became arguably the greatest songwriting partnership in popular music.

What a gift he had, seeming to exhale melodies. What a remarkable, innovative bass player, to boot. What unforgettable harmonies (so tightly wound, so perfectly matched) he and John Lennon (and George Harrison) brought to us out of their scrappy Liverpudlian backgrounds, all grounded by Ringo’s perfectly-honed fills and metronomic backbeats.

But the thing about Paul McCartney in his youth is this: he was a much tougher dude (and a better lyricist) than we remember. He was very much a driving backbeat himself — an original “lead from behind” sort — who acted like he was giddy to be along for a ride when in fact, he often had control of the wheel.

He was the one who taught Lennon how to tune a guitar, how to play actual guitar chords, not banjo chords, how to find chords on a piano and grow from there, and even how to write a song. He was the one who brought George Harrison in as lead guitarist. He was the one who argued vociferously against Stu Sutcliff — a talented artist but no bass player — remaining in the early band, to the point of physically brawling with him in the middle of one of their roustabout, amphetamine-fueled all-nighters in Hamburg, while the band played on. He’s the one who made bold to replace Pete Best with Ringo. He was the one, ultimately, who decided the Beatles would tour no more.

If Lennon wore the Beatles crown, McCartney was the diplomatic force behind it — the guy who would get his way while making everyone else think an idea was theirs. He maneuvered quietly in background, with a sometimes Machiavellian determination to satisfy his own ambition, to get precisely what he wanted. And all the time he had that strangely beautiful look — big sloping eyes, full lips, slightly tipped nose — all packed into a smallish face that, along with the moptop cut, made him look a bit like a human anime cartoon, one that people responded to because…well, that’s what babies look like, right? And who can resist a baby?

Lennon didn’t have the advantage of an innocent appearance from which to launch a march, nor did he possess guile. Every thought John Lennon had was all over his face and out of his mouth before he could stop himself, and it was constantly getting him in trouble, particularly during the Beatles’ last (utterly miserable) tour of the USA in 1966, during which the band — already weary of playing before fans more interested in experiencing a psycho-sexual catharsis than in actually listening to their music, endured death threats, demonstrations and more thanks to a series of interviews (“How Does a Beatle Live?”) given in March of 1966, and which had caused narry a ripple in the UK when published.

In the United States, particularly in the American South, Lennon’s quite true observation that the band was “more popular” with the youth than Jesus was interpreted as “We’re bigger than Jesus” and the press happily fanned the sensational flames, because that’s what the press does, and what they did from tour stop to tour stop. “Do you really think you’re bigger/more important than Jesus?”

As you can read in the interview, Lennon never meant that.

Experience has sown few seeds of doubt in him: not that his mind is closed, but it’s closed round whatever he believes at the time. “Christianity will go,” he said. “It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ‘n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.” He is reading extensively about religion.

As a Christian, and a music fan, I may not like reading any of that, but from his perspective, sitting on the edge of Europe at that time, Lennon’s words seem prophetic. And then, of course, the Americans more or less made his point for him about Jesus’ disciples being “thick and ordinary.”

Still, the Beatle making the harshest remarks about religion in 1966 was not Lennon, who really seems like he was just letting his mouth run at Maureen Cleave, but Paul McCartney, who wasn’t simply releasing words into the ether; he was enshrining a complete idea into a piece of lasting art, and the idea was rather stunning for both the time, and the medium: The Church is failing in its mission to save; it is becoming irrelevant to people’s lives because it is too self-concerned, too insular, too busy protecting its own interests — darning its socks — while the world spins and the pews empty, and humanity grows ever more lonely, more isolated, and social interaction becomes more fleeting, more guarded and inauthentic (wearing faces kept handy by the door…or the twitter Facebook feed) until it disappears completely, and no one is saved.**

McCartney, baptized a Catholic but raised in faith haphazardly even before his mother died, thanks to his parents “mixed” marriage, nevertheless read the sign of the times from his reluctant seat near the exit, but no one seemed to catch it (or to mind it), because it all sounded so pretty, just like him.

All of McCartney’s melodies from that early Beatle era, right through Rubber Soul and Revolver, sounded like we’d always known them — they flowed so effortlessly and instinctively into us that they seemed instantly familiar — but the songs themselves often contained much rougher lyrics than people really grasped. “Yesterday” is not a pretty love song; it’s an expression of searing regret for words and actions that cannot be taken back and so must be lived with. “I’m Looking Through You” and “You Won’t See Me” sound like happy, jangly pop fluff but describe a serious relationship in descent, about to crash-and-burn. “For No One” is simply brutal, like “Yesterday” it is melodically and instrumentally innovative to the point of fascination while its lyrics are an unflinching admission that a relationship is utterly dead, that the players are going through the motions and likely have been for a long time, and yet the idea of that ‘love’ still has a lingering hold on the mind. Devastating.

Young Paul McCartney was a sharper customer than we appreciate, the razor in the bright and shiny apple. Read his turn being interviewed by Maureen Cleave, where he is whip-smart, observant and ready to argue or charm as need be. Look at his statements — about race, gender, conventionality, and morals. They should have come up during the American tour, but never did:

[America is] a lousy country where anyone who is black is made to seem a dirty n*gger. There is a statue of a ‘good Negro’ doffing his hat and being polite in the gutter. I saw a picture of it. […] “There they were in America, all getting house-trained for adulthood with their indisputable principle of life: short hair equals men, long hair equals women. Well, we got rid of that small convention for them. You can’t kid me the last generation were any more moral than we are. They hid it better. If you wheedle it out of people they were just as bad as we are, only they grew out of it.”

“Perhaps,” he said, with the air of one hitting on the truth, “perhaps they grew too tired for it.”

Lennon’s remarks may have been put forward for examination specifically because he had willingly played cipher before, and it was so easy to get a rise out of him, but — as with the fisticuffs in Hamburg — McCartney was the one dealing real blows to the social fabric, fast jabs that left interior bleeds no one could accurately trace, while the band played on.

It was, sadly, a capacity he seemed to lose, once the band no longer played.

**NOTE: Interesting aside about “Eleanor Rigby.” At first McCartney resisted the idea of a string accompaniment. When George Martin finally convinced him it would work McCartney agreed on one condition, “No vibrato, as much as possible, no vibrato. I want it to bite.” Yeah, he did.

See also: How Beatlemania Touched the Mad Eros of the Cross

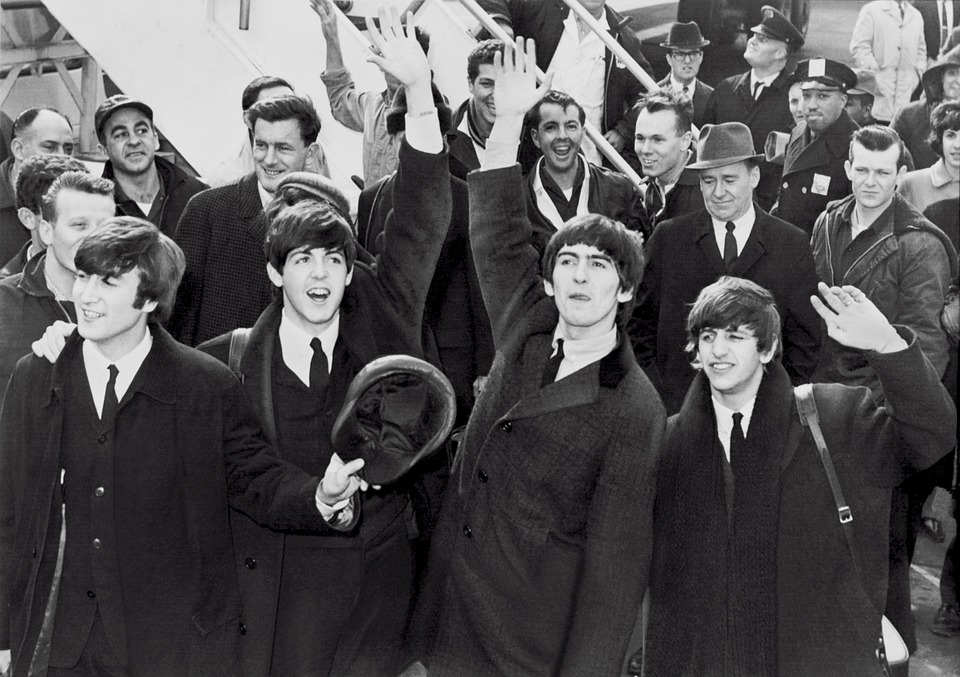

Featured image: Undated photo reportedly taken by George Harrison

3 Comments

How Beatlemania Touched the Mad Eros of the Cross - The Anchoress · June 20, 2019 at 12:38 pm

[…] READ ALSO: “No one was saved”: How Paul McCartney Surpassed Lennon’s Critique With 4 Words […]

The Quality of Evangelism and Preaching Does Not Depend Upon a Pulpit – Saint Charles Victory Park · August 8, 2019 at 6:15 pm

[…] stupid to me. I’d rather write a piece on the Catholic import of “Eleanor Rigby”—something that over 20,000 people have read (and can access again if they want)—than preach on […]

So... Couple things on my mind tonight... - The Anchoress · October 9, 2019 at 10:17 pm

[…] But what if the broken people — sorry, Paul (McCartney) but we’re talking broken, not lonely people (although most broken people probably are lonely on some level, and lonely people probably […]

Comments are closed.